The pandemic hit college campuses in a hard and multi-faceted way.

Students returned home, if they could, leaving belongings abandoned in quickly vacated dorm rooms. When we first conceptualized this series in early April, campus staff and administration weren’t even thinking about a fall return to campus, they were focused on students traveling home, finding a safe place to stay, and the return of personal property. Colleges also acted quickly to get classes up and running again, finding electronic platforms upon which they could place materials that sought to educate students, who were now redistributed globally. One professor from a small school in Pennsylvania remarked that he was given five days to transition all of his materials on-line, and Principal Matt D’Amico, who sits on the Foundation Board of Howard Community College, reported (in early April) that HCC was trying to come up with a solution, “and fast.” Campuses didn’t know if the answer was more online courses, fewer students per classroom, or a series of new procedures that would ensure campuses, classrooms, and dining halls were safe. When it came to planning, where would they even begin?

It seems, during this pandemic, that the easiest place to begin is with distance. If we separate people from one another, be it at the grocery store or the movie theater, they can’t infect one another. The measurement, six feet, is tangible. It’s easily measured and evaluated, without chance for subjective interpretation. So, it’s not surprising this is where college campuses opted to start as they thought about what would come next in terms of returning students to campus.

Right or wrong, density has become a focus, where according to Principal Tom Zeigenfuss “the natural reaction” is to reduce concentrations of individuals. Reduction in density, though, is difficult to achieve on campus, where vertical residence halls, roommates, and shared bathrooms are institutional hallmarks and realistically speaking, the only way to practically house students. In addition to housing, residence halls are designed for community formation, often with common areas or study rooms to encourage chance meetings and facilitate socialization. But if campuses decide to take away opportunities for gathering, what happens to the college experience? College is when young adults can find their own communities and connect with others. If these opportunities are eradicated, they won’t just have trouble finding new communities, there simply wouldn’t be any communities for them to find. Tom speculates that a reduction in common spaces would reduce the sense of community and opportunities for gathering. “For a college-age population that’s already combatting issues of online comparison, isolation, and FOMO, changing design to eradicate or greatly limit gathering spaces would likely make this condition even worse.” So, while physical separation may make us feel safer in the short-term, it could also change the way we relate or interact with others permanently.

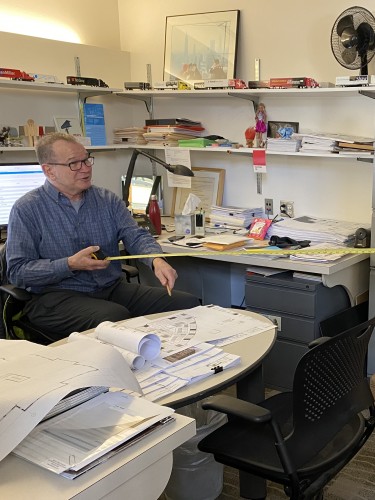

Both Tom and Principal Marvin Kemp believe it may be over-kill to try and design for a pandemic like COVID-19. “As architects, we can’t act in a reactionary manner through design, as we must balance the near-term response with longer-term solutions,” Tom says. This sentiment of acting responsively, but not drastically, is similar to how we, as a Collective, feel about the architecture and planning response to COVID in terms of workplace and public space, too. Marvin agrees, believing any redesign should be done with “flexibility designed for changing needs.” Several projects have already adopted this approach, Winston Salem State University asked Design Collective to design flexible spaces, like “generic labs that can be used for multiple purposes while providing adequate computational space for changing lab needs.” Marvin explains the concept of space needs analysis, “there are ways to take spaces our clients currently have and quickly make them safe…we program classroom spaces for 20-25 square feet per student. Clearly, that will not allow for appropriate 6’ social distancing. We can quickly take the dimensions of the space and the furniture in the room and help clients re-program the space to allow for a minimum 36 square feet per student or more and tell them what their class size should be for any space on their campus.”

This type of analysis is done at a lower cost than a complete redesign, as design modifications are likely to be expensive. Traditional style residence halls (typically long corridors with a shared bathroom along the hallway), may present the greatest challenge, due to the shared bathroom component. Not only is it the consideration for architectural redesign, but a “budgetary conundrum for schools, whose profit statement is likely based on max occupancy,” says Anthony Savia, Vice President for Administration & Finance at Bowie State University. Housing students in singles-only would present challenges beyond the budget sheet, like how schools would deal with the students who still needed housing, or the operations cost related to more housekeeping staff needed to wipe down shared surfaces, furniture, or gym equipment. Similarly, Tom speculates that if schools took the approach of implementing more advanced and expensive mechanical systems in their projects, that would furthermore lead to additional costs of more robust maintenance contracts required for upkeep, and testing and monitoring of equipment. He notes that some of these strategies, while presenting significant economic challenges, may be appreciated by students and parents in the very near term. These same issues apply to renovating existing campus housing as well – reducing doubles into singles, adding automated equipment for touch-free surfaces, creating greater air exchange rates, and increasing housekeeping services are all approaches with both short-term benefits and significant cost implications.

And capacity may in fact be an issue, as students in 4-year colleges may opt to stay home, or closer to home. Community colleges need to be prepared for a potential influx of students, as they may see an increase in enrollment and growth similar to that during the 2008 recession. According to Savia, Bowie State University reports enrollment applications are up from last year, and the housing application is consistent. This makes sense for a school like Bowie State which is in Maryland, where lots of college students typically venture out of state, and a swap to in-state college would guarantee in-state tuition. Currently, Design Collective is designing a 500+ bed living-learning community on Bowie State’s campus, and Savia admits he’s “glad to have excess capacity.”

In the interim, before new student housing facilities are completed or new buildings designed, there may simply be a focus on amenities to alleviate density and infectious disease: sanitizing stations at the ready, replacing difficult to clean surfaces like carpets or ceiling panels with alternative materials, dedicating wings of residence halls to temporary student isolation, rearranging furniture, or putting up dividers in common areas. Other solutions can be more taxing in terms of cost, benefit and infrastructure, like increasing air exchange rates, which Marvin notes has “an environmental toll as we will be spending more on energy while we exhaust more air from our buildings rather than recirculate it.” It reminds us that, at this point, any solution seems to demand a trade-off.

What it comes down to, is as Savia puts it, there’s “not a lot of guarantee right now.” Institutions are cautious about debt, money is tight, and short-term reduced density will make projects expensive and raise rents. Affordability is already and may continue to be a factor with amenity spaces, fitness rooms, and classrooms becoming bare bones until pricing balances out. Marvin reflects on how schools are thinking of shifting, deciding to fund projects they believe to be most essential. “The interesting part,” Marvin says, “is how each client determines what is essential.” This definition of “essential” pinpoints the importance of communication, between clients, colleges, contractors, and architects. While we may all perceive the same risks, we need to look to one another to identify priorities and differentiate between need and want.